Arnold Goldstein sold seven homes in his first month as a Realtor, and a record 60 homes in his first year. But his greatest joy came from teaching other agents to be successful

by Kevin Cody

Chris Broadhurst was a senior at Mira Costa High School in 1975, when she joined the Shorewood Realty family in its property management department. The office was in a small beach cottage on Artesia Boulevard, conveniently across from the high school.

Broadhurst answered phones, put boxes of canceled checks in numerical order, and cleaned houses.

After listening to her on the phones, owner Arnold Goldstein suggested she get a Realtor’s license. Callers wanted information on listings, and it was illegal to share Multiple Listing Service information without a license. He offered to pay for her license if she would attend the training program he had created.

The first class was on listings; Goldstein was the teacher.

“I was 18 and looked 16,” Broadhurst recalled. “At my first open house a buyer asked when my parents would be home. I was so embarrassed, I said they’ll be back shortly.

“I asked Arnold how to make people take me seriously. He said know more than the other agents. And never guess. If you don’t know an answer, tell the buyer you’ll get back to them.”

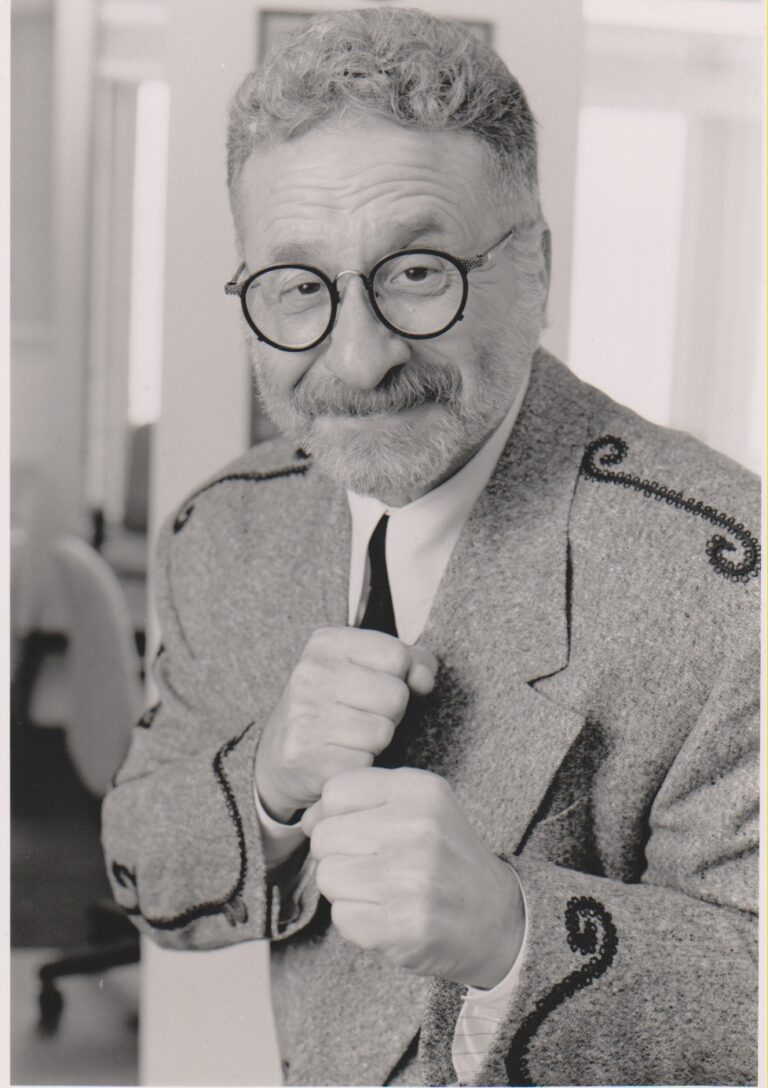

The ever fashionable Arnold Shorewood at work in the ‘70s, when the Afro became popular. Photo courtesy of the Goldstein family

“On my first listing call, Arnold offered to go with me. He folded himself in his Versace suit into my powder blue VW bug. I was wearing a dress my mother made me because that was all I could afford.

“We sat down at the homeowners’ kitchen table in the Candy Cane Lane section of Torrance. I was so nervous I was hyperventilating. Arnold sat next to me, quietly giving me reassuring looks. After my presentation, I slid the contract across the table to the sellers. They signed it.

“Even though this was an era when parents didn’t talk to their kids about money, when my dad found out how much I earned my first year, he told me it was more than he made at Xerox.”

Broadhurst told the story at Goldstein’s memorial on Monday at Hillside Memorial Park. Over 300 people attended, most members of what Goldstein called his Shorewood family. Goldstein passed away on Tuesday, January 23, at age 91, from conditions related to old age.

Broadhurst remained at Shorewood until Goldstein and partner Larry Wolf sold the company in 2014.

Shorewood Realtors owners Arnold Goldstein and Larry Wolf with Chris Broadhurst, who started with Shorewood when she earned her Realtor’s license at 18. Photo courtesy of Chris Broadhurst

Ed Kaminski spoke at the memorial about what it meant to be a part of the Shorewood family. He was with Shorewood from the early ‘90s until it sold. He opened his own office in Hermosa Beach, and by coincidence, was recognized Monday night at the Hermosa Beach Chamber of Commerce Best of Awards as Realtor of the Year.

“Once you were in, you didn’t leave. And if you did, well…we won’t go there,” he said.

“Arnold lived and died to recruit agents. He wanted to hear the word ‘yes’ as badly as an agent wants a yes on a Strand listing.

“Mentoring doesn’t adequately describe what he did. Fred Zuelich called Arnold our shepherd. He guided us to wealth we never would have reached on our own.

“He did it by teaching us the work ethic of the ‘60s. It was all about hard core, pounding the pavement every day, being disciplined, and never giving up, not taking no for an answer, and if you did, knowing there was always a yes around the corner. So go find it.”

“Arnold had five offices,” Kaminski recalled, “each with its own personality. He loved them all the same, like they were his children.

“The Highland Manhattan Beach office was the rich kids’ fraternity. They sold expensive homes, the homes over $500,000. It was led by Reyn Park, one of the greatest agents in the history of South Bay real estate. Reyn was a testament to Arnold’s ability to recognize talent, and retain it.

“The A-frame office on Manhattan Beach Boulevard looked like it was trucked in from a mountain ski town. It was totally out of place. Its agents were the OGs, the hardest working people in the company.

“The Hermosa office on Artesia was the farm team, the dumping ground for agents who probably weren’t going to make it. It was an old bank, with a vault in the back. In the vault was a bookshelf, and on the top shelf, behind the third book from the left was the ‘calming juice,’ for days when things got crazy, which was every day.

“We called the Redondo office the suburbs because it wasn’t in Manhattan, and wasn’t in Hermosa. It’s where Arnold had his office. He didn’t want to be isolated in the corporate office on Duncan. He wanted to be in the field, with the troops.

Former Shorewood Realtor Ed Kaminski accepts the Hermosa Beach Chamber Realtor of the Year award, on Monday, the same day he spoke at his mentor Arnold Goldstein’ memorial. Photo by Kevin Cody

“The fifth office, on Sepulveda in Manhattan Beach, was an outlier office with just two agents, Raju Chhabria, and myself,” Kaminski said.

“I was with Raju at Century 21 when Arnold convinced Raju to close his office and join Shorewood. I’m not sure Arnold even knew I was part of the package. Raju quickly became Shorewood’s top agent, and I was number 2. It’s a testament to how great a leader Arnold was that he was able to not only lasso the South Bay’s top agent, but to retain him,” Kaminski said.

Goldstein preferred not to hire veteran Realtors.

“I hired some experienced people and found I got their bodies but not their hearts and minds,” he told Beach Reporter editor Paul Silva in a 2013 interview. “I learned I could take the right people off the street and train them, teach them where to go, what to do and how to do it.”

“When I sit with someone, it’s not across a desk. We sat side by side. I might have trouble talking socially at a party, but if someone comes into my office they are there for two to three hours… I feel responsible for them. I have their lives in my hands. Maybe I’m being overly dramatic, but I am going to do whatever I can do to make sure they succeed,” he said.

During the defense industry slowdown in the early ‘70s, Goldstein struck a rich vein with disenchanted aerospace workers.

One was Larry Wolf, who became Goldstein’s partner in 1979. When they sold the company in 2014, it had grown to seven offices and 350 Realtors. It was the eighth largest real estate company, by dollar volume, in Los Angeles County, and the 75th largest in the country.

Another aerospace recruit was Audrey Judson, an engineer at Hughes.

“We respected Larry. But if you needed someone to talk to, you went to Arnold. At office meetings he was empowering. He loved to get the sale,” she said.

After he retired, she continued to call him for advice.

“He didn’t die of old age. Selling Shorewood is what killed him. He told me it was the biggest mistake of his life,” she said.

Within two years of Shorewood’s sale, the buyer who promised Goldstein and Wolf he would preserve the family culture, filed for bankruptcy.

Goldstein was born in Detroit in 1933, the oldest of four children.

“My dad was a milkman until I was 12. He had a horse drawn wagon. If I was lucky I could get up at 3 or 4 in the morning and help him deliver milk,” he told Silva.

He moved to California with his mother, brother and two sisters in 1953 when his parents separated. He studied fashion at Woodbury College in Los Angeles, and worked with William Travilla, designer of the famous white dress worn by Marilyn Monroe in “Some Like It Hot.”

Arnold Goldstein with wife Homeira and son Joshua at an evening organized by South Bay Realtors in 2019 to honor Goldstein and South Bay Brokers co-founder Jack Gillespie with Lifetime Achievement awards. Photo by Kieron McKay (DIGS)

He left fashion after realizing his gift was in sales, but fashion remained an obsession throughout his career.

“Men had to wear dress shirts. No shorts or tank tops,” Broadhurst said. “His company was number 1, and he wanted its Realtors to dress like we were number 1. He believed when a buyer walks into an open house, Realtors should stand out by the way they dressed.”

Goldstein made sure he stood out with designer clothes, not just by familiar names like Versace, Chanel and Valentino, but also Japanese designers Yohji Yamamoto, and Issey Miyake; and French designer Thierry Mugler, designers accessible only to an elite class of buyer.

Both Goldstein and Elton John wore a size 54, which made them competitors. When a Beverly Hills store received a jacket they thought both would like, their first call went to the one who had recently tipped the best.

In 1964, Goldstein was 31, living in West LA, and selling automotive parts when his friend, Herb Rosenkrantz, convinced him to get his real estate license. He then joined Rosenkrantz’s Harbor Realty on Pier Avenue in Hermosa Beach.

“I didn’t know anybody, and didn’t know the street names, but somehow I had seven sales and nine listings during my first month,” Goldstein told Silva in the 2013 interview.

That first year he sold 60 homes, a South Bay record that will never be broken.

Arnold Goldstein and Morrine Robey at Goldstein’s 80th birthday in 2013. Photo courtesy of the Goldstein family

In 1969, he opened his own office in Hermosa Beach. Shorewood was the name of an upscale community in Wisconsin, where his wife Irene was from. Over the next four years he opened four more offices, and hired over 100 Realtors.

But his prodigious work habit came at a price. His marriage dissolved, and he would remain single until a blind date 15 years later.

The future Mrs. Goldstein was a descendent of the Qajar royal family, which ruled Iran until 1923. She was raised in luxury and maintained that lifestyle after earning an MBA at USC.

She worked in finance for a succession of companies, including Arthur Young, Tiger International and Harman International before founding her own finance company, HAF, named after her initials. HAF’s office was in the 1888 Century Park West financial center in Century City.

She had been separated from her husband for nine months when her friend Marsha Goodman convinced her to go to dinner with “a harmless gentleman” who sold real estate in Manhattan Beach. Dinner was at the Bel Age Hotel, before it was popularized by Gordon Ramsey, and Beverly Hills 90210.

She did find him “harmless,” but also overly talkative. And he didn’t like to travel. She had spent much of her time since her separation sailing with friends, including Goodman, off the coast of Turkey, and on the maiden voyage of a friend’s yacht, from its Italian boatyard to his home in Gibraltar.

She accepted Goldstein’s invitation for a second dinner, later in the week, only because he had suggested the West Beach Cafe in Venice, her favorite place for after dinner drinks with girlfriends.

At the second dinner, the man who excelled in convincing people to say yes was told no to his offer of a Hanoverian show horse named Elecktron, no to his offer they have a child together, and no to marriage.

“I’ll tell you a funny story,” Homeira said this week when recalling the couple’s courtship.

“After he proposed to me, I was on the walkway to my office in Century City, when a man walking the other direction, with his attorney, stopped me.

“He said, ‘I need to meet you.’ I tried to ignore him, but he said he had some financial matters he thought I could help him with.”

“While we were discussing his businesses in my office, he asked if I’d like to attend an entertainment charity dinner that evening. I said no. Then he asked if I’d like to go to the Lakers-Celtics game on Sunday. I loved Larry Bird. So I said yes.”

“The day before the game, I had lunch with Marsha and told her how odd it was that after not dating for a year, I had two dates, both with men named Goldstein.”

“Martha looked at me and said, ‘Oh no. Arnold has a brother.’ I told her there are lots of Goldsteins, and Arnold was dark and the other guy is blond and blue eyed.”

“At the basketball game the next day, I asked if he had a brother. He said, ‘You mean Arnold?’”

“I told him he had asked me to marry him, and had offered to give me a horse, and have his child. But I had said no to all three. He said, ‘Good. Don’t marry him. He’s a confirmed bachelor and not a nice man. Marry me.’”

Two years later, at the Four Seasons Hotel in Beverly Hills, moments before Arnold and Homeria were to exchange vows, Arnold’s brother told Homeria, “It’s not too late. Marry me instead.”

Arnold Goldstein and Shorewood Realtors Realtors celebrate his 80th birthday in 2013. Photo courtesy of the Goldstein family

During the couple’s courtship, on a ski trip to Aspen, Homeria understood that her new in-laws were not just his brother, but also the 400 agents who made up the Shorewood family.

“Arnold had bought both of us gorgeous Bogner ski outfits. Arnold had never skied, but we planned to stay for five days. On the second day he said, ‘This is not for me. You enjoy yourself.’ He called me the next day from the office. He said, ‘This is where I belong.’”

Homeira did not want to move to Manhattan Beach.

“I wasn’t a beach person. There was nothing there for me,” she said.

“Arnold drove me to a vacant lot on a corner overlooking the Santa Monica Bay, and said this was where he was going to build me a house.”

Six years later when the house was finally completed friends who came to visit said they went to the address, but couldn’t find her home. There was a monolith on the corner

The home was designed by architect Pat Killen, whose designs included a new Skechers Corporate headquarters in Manhattan Beach that the third-largest shoe company in the country rejected as too expensive to build; and a Manhattan Strand home neighbors call the jewel box, because it is tiny, and its floor to ceiling windows display everything inside. Only by careful navigation behind strategically placed room dividers, can occupants not themselves become part of the display.

Killen’s design for the Goldsteins was a three stories tall arrangement of alternating columns and mullioned windows covered by shades to prevent sunlight from damaging the art inside. The only exterior embellishment is a nod to art deco over the front entry. Towering Washington palms throw dancing shadows across its projection-screen gray walls.

Homeira said one of her husband’s practices was to immerse himself in whatever interested his close friends.

The prize winning horse he offered her was from a breeding stables he bought because a woman he had dated loved horses.

In her case, he immersed himself in her passion for collecting art. But it wasn’t an entirely new interest for him.

Arnold Goldstein and Morrine Robey at Goldstein’s 80th birthday in 2013. Photo courtesy of the Goldstein family

“He drew beautifully. When he waited for me at my Century City office, or when he was waiting for me to go to dinner, he would sketch. He drew hands, faces, flowers, anything he saw, he’d draw. Then he would throw the drawing away.”

Homeria may have saved some of the drawings, but if she did, she said, she doesn’t know where.

The house was not designed for children. Its floors are French limestone, with an open floor plan to better display sculptures. But on a rare overseas trip with vintner Robert Mondavi and his wife Margaret, to the champagne house of Pol Roger, made famous by Churchill, Homeira was surprised to learn she was pregnant.

“Arnold convinced me to close my financial firm because I would feel bad if time passed, and I wasn’t there for our son,” she said.

Arnold was “over the moon” with excitement, Shorewood family members recalled.

Lynn O’Neil and Chris Broadhurst with Arnold Shorewood in his retirement.

Goldstein remained sharp, and his former agents continued to seek his counsel until he fell over Thanksgiving.

In 2021, a group of Shorewood veterans founded Pacifica Properties Group, and sought his counsel.

“We were tired of the big companies trading Realtors like cattle,” said co-founder Karynne Thim, who started at Shorewood in 1993. “His big thing was to treat the agents fairly. After all those years, that’s what it all boiled it down to.”

Goldstein is survived by his wife Homeira, their son Joshua, and grandson Silas; his former wife Irene, son Mark, and granddaughters Jordan and Mia. His daughter Suzanne preceded him in death. ER