Announcing a $100 million fund drive to find jobs for the permanently unemployed, Potter's House Evangelist Jakes TD told Mitchell Schnurman: dallas morning news This week: “If I have to go to work in the morning, I won't be wandering around town at night with a gun.”

“Even if it starts with driving a truck, if you can get people into a room. You can't climb a ladder unless you're near the stairs.” — TD Jakes

Tweet this

Mr. Jakes told Mr. Schnerman. There is a sense of hopelessness and hopelessness in underserved communities. ”

That's almost all true, and Jakes is a hero for saying it and taking it on as a mission. It's all about work. The conundrum of work availability and inability to work is at the heart of the south Dallas tragedy. But the puzzle is deeper and more complex than just a matter of opportunity.

Let me just say this: It's not going to be white people who understand this. Not here, not now, not for a while. In short, Jakes, a black man, is intervening where he is most needed and can do the most good.

In 2013, when the city was pouring all its public resources into building an exclusive, ultra-expensive private golf course south of Dallas, I took a closer look at the employment numbers in the census tracts surrounding the site. The unemployment rate was significantly higher than that in white areas on the city's north side, but that wasn't a number that shocked me.

The truly surprising statistic concerned what the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics calls the “non-labor force.” The BLS defines people not in the labor force as “retirees, students, people caring for children or other family members, and other people who are not working or seeking employment.”

Figures from the census tract near Golden Golf Course show a staggering 60% of the population is not in the labor force. That's twice his rate in a typical neighborhood in the white half of the city.

The last part of the definition, “not working or seeking work,” includes a category called “discouraged workers.” Strictly speaking, these people refer to people who have given up on finding a job, but perhaps the definition can be expanded to include people who never had the slightest hope or expectation of finding a job in the first place. Should. We are confident that we can all agree to that amendment without much controversy.

But the definition of “not in the labor force” also needs to include another category or description that causes everyone to pull out a knife every time that word is uttered: people who don't want to work. And I would like to refine even that, based on personal experience, to something closer to people who don't want to work in the kinds of jobs that are available to them.

What personal experience would such a thing be based on? About me being a white dude? Well, I can accept that to a certain extent. My brothers never called me “white,” but you might remember the rest of the phrase as something of a nickname around the house.

But listen, I've also been dealing with the issue of work availability for years in Dallas. Jakes believes he knows what he's talking about when he says his message is very different from what influential black leaders have told voters in the past.

Jakes told Schnerman: You cannot climb the ladder unless you are near the stairs. ”

This is literally the opposite of what Dallas County Commissioner John Wiley Price told voters more than a dozen years ago. At the time, Price was heavily focused on a successful campaign to shut down a California entrepreneur who wanted to develop a new large-scale distribution and warehousing center in Price's district.

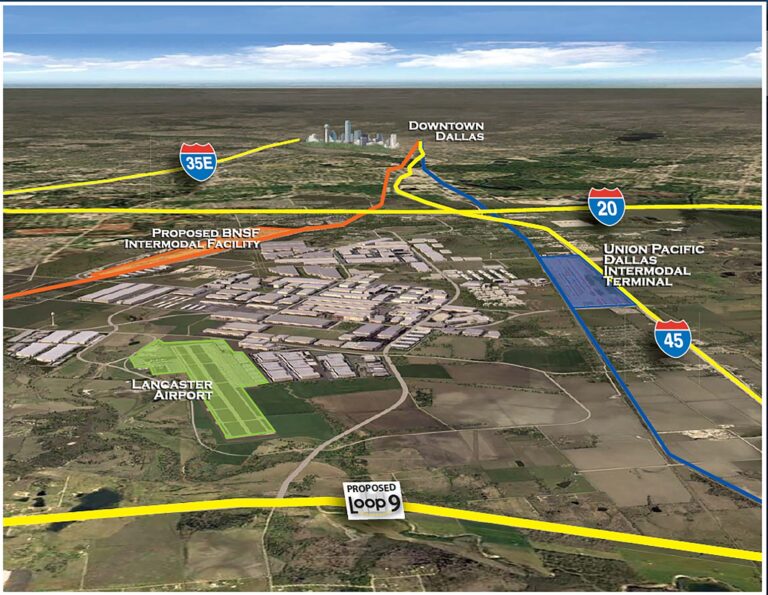

Richard Allen, a nationally respected logistics industry leader (warehousing and shipping), plans to build 6,000 acres south of Dallas, bringing 60,000 new, high-quality jobs to Price's district. The mentioned development was proposed. But Mr. Allen's project would be in direct competition with a similar operation in Fort Worth owned by Dallas' powerful (and white) Perot family.

dallas morning news He campaigned against the South Dallas project in both editorial and news columns. In subsequent court testimony, executives representing Perot's interests testified that they viewed the south Dallas project as a serious potential competitor.

Mr. Price, who has ties to the Perot family through his campaign adviser Kathy Neely, joined the effort to kill the Allen project, but he never publicly said he opposed the project because of his ties to the Perot family. In a personal appearance and written statement on South Dallas radio, Mr. Price said that the hourly jobs provided by the project (60,000 of them) have a derogatory connection to slavery. He said he was opposed to the project.

Dallas County Commissioner John Wiley Price, a respected leader in the southern Dallas area for a third of a century, has despised hourly jobs as a legacy of slavery.

Brandon Thibodeau

“During slavery, everyone had a job,” Price wrote in a letter to Allen.

He meant it. Of course he had other objectives, but he meant what he said about slavery and employment. I argued with him on the phone about it. I said, “During slavery, no one had a job.”

he said: “They had a job. What was it called then?”

“It's called slavery. They stole lives,” I said.

“Slavery, Jim, it's an institution. And the hard work of the institution paid off. And traditionally, working is a job. I'll tell you the nickname that most African Americans have for their work. That is called slavery.”

These were terrible words from a leader who enjoyed great respect, power, and influence in his realm. He wasn't just saying this to me, this white guy. He was saying the same thing to his constituents on the radio, in church, on the stump.

“I'll tell you the nickname most African Americans have for their job: It's called Slave.” — John Wiley Price

Tweet this

It would be foolish to believe or suggest that Secretary Price's words did not have a strong impact on those who heard or read them. He has been re-elected by an overwhelming majority for his 36 years on the District 3 County Commission seat, which covers his third of south Dallas and all of the southernmost and southeastern parts of the county outside city limits. I did. Mr. Price's influence as the city's longest-serving and most powerful black official extends far beyond the boundaries of his own district.

He was acquitted of federal corruption charges three years ago in a high-profile trial that uncovered much of the evidence in the Perot case. It would be easy to dismiss his statements about labor and slavery as a cover story. And that would be a big mistake.

Price grew up in Forney, east of Dallas, when it was still a dusty cotton town. A slavery-like indentured servitude called debt peony continued in that part of Texas into the 20th century, according to the Texas Historical Society and other researchers.

During the fall harvest season in the early 1960s, when Mr. Price was a high school student in Forney, black students were expelled from segregated public schools to work on the farm. White students stayed in class and studied.

Price once told me that when he looked out over the endless rows of cotton, all he could see were black faces and black hands bent over the cotton, black backs dragging long sacks, while all the white children stuck their noses in books. He said he had gone back to school. , it certainly looked like slavery. What I understood was that for poor rural and small-town African Americans, the shadow of slavery was much more recent than the white guys in Detroit imagined.

So when we face the challenge of working, taking on hard and sometimes even dirty work in order to enter the mainstream economy, we do not arrive clean. Not me, anyway. Depending on your skin color, this may not be the case.

First, even if slavery was abolished as an institution, the indignities and injuries it caused never ceased. On top of the original horrors of slavery were layered a century and a half of Jim Crow, slammed doors, humiliation, and crushing rejection.

Indeed, the strongest black families marched straight toward it with their backs down and fierce determination. But what percentage of us are the strongest? How many of us are the strongest white people?

In fact, the term “discouraged worker” seems tame when you look at the harsh rejection and rebuffs meted out to black job seekers over the past century and a half. Words closer to despair, bitterness, or even pain seem more appropriate.

Don't get me wrong. I slightly disagree with the price. I have voluntary immigrant roots. I have always thought of the true promise and charm of America, until I could buy a good wheelbarrow and pick up scrap metal for a dime, find an abandoned broken wheelbarrow, and pick up a dead dog for a penny. So I had to see this as an opportunity to get it to the rendering plant. This is how dreams begin with work.

I think I understand why Price said that. But I also believe that Jakes is right. A life without work is a ticket to hell on earth. And it's not just a guess. A quarter-century of robust research has found that unemployment rates are far more closely related to crime rates than poverty.

In the late 19th century, the pioneering French sociologist Emile Durkheim proposed a link between outdated trading guilds and a condition he called anomie, a kind of disconnection and lack of a deep sense of belonging, but later Durkheim linked it to suicide. I've been wondering if suicide isn't a cousin of accidental murder, and there's a sense that it doesn't mean anything anyway.

Jakes says everything more directly. “If you have to go to work in the morning, you won't be wandering around the city at night with a gun.”

And he can say it. Here's the reality. What Jakes is saying can only be said from within the black community. I already told you my nickname.