It was a breezy evening in Paris the first time I met the filmmaker and multimedia artist Ja’Tovia Gary in May 2022. We were at galerie frank elbaz in the fashionable and historic Le Marais neighborhood. The gallery was holding an opening for “partus/chorus,” a three-woman exhibition she had curated that also featured Eniola Dawodu and Doreen Lynette Garner.

Gary’s as you yield her your body and soul (extract) was the central work of the show: a hollow pyramid cocooned in plucked cotton (which she had sourced from a farm in North Carolina), inside of which were handwoven cushions for visitors. Inside, too, were dried wildflowers and more tufted cotton. Projected onto the outside was a video collage titled Mitochondrial Montage—flickering family photographs and video clips layered and intercut with hand-animations and archival footage—that made the white room glow pink and ruby. The gist was hard-hitting, but the effect was hypnotic. I felt like I had entered a trance.

Even in the elegant chaos of an art opening, Gary was hard to miss, with her head strikingly shaved, wearing a blue-and-white toile dress and green Camper sandals with straps like fat snakes. I introduced myself and stammered something about our shared Dallas connection and wanting to write about her before she was whisked away to an after-show dinner for senior gallery staff and special guests at a bohemian-chic Thai spot nearby. “Reach out!” she called as we went our separate ways.

Elbaz would later place Gary’s pyramid with the august Fondation Louis Vuitton. He would like to get another exhibition on the books. But she’s busy. She stays busy.

In February, Gary mounted a solo show at the ultra blue-chip Paula Cooper Gallery in New York and completed work for her current solo exhibition at the Dallas Museum of Art, “I KNOW IT WAS THE BLOOD,” that opened in April and will run through November 5. Later this fall, the Museum of Modern Art in New York will display her most well-known installation, The Giverny Suite (2019), a piece acquired from a previous Paula Cooper show.

And then there is the feature-length film she has labored over for almost 10 years. The dozens of hours of footage collected over more than a decade began, as she says, as “an exploration into my mother and our relationship.” But it eventually became a memoir of multigenerational trauma and a personal salve, a journey of revelation and (hopefully) repair. A film she moved back home to Dallas from Brooklyn in 2019 to—finally—complete. Yes, there is also that.

In Paris, I got a brief glimpse of what Gary’s life is like; the opening was not the first time she’s been whisked away. To see the world in which she moves—intellectually and artistically—is to brush elbows with filmmaker Arthur Jafa and the sculptor Simone Leigh, who represented the United States at the 2022 Venice Biennale. Leigh was behind Loophole of Retreat, a several-day gathering of Black female artists, writers, and academics on the little island of San Giorgio Maggiore last October during the Biennale.

“It was kind of dreamy,” Gary says. “It felt surreal.” To convene in a garden drinking Aperol spritzes after a short boat ride “and then you see [the iconic Black feminist artist and writer] Lorraine O’Grady kind of move through the space, and it’s like, what’s going on?” And what’s going on when respected scholar and writer Saidiya Hartman is in the second row of a lecture space, a hero looking back at Gary as she speaks? These women had helped her lay the foundation for her work. She felt nourished by the collective, the intellectual sisterhood.

But Gary has always been in artistic circles that fizzed. The first was at Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing and Visual Arts.

Gary transferred into Booker T. as a junior from Cedar Hill High School in 1999 in order to pursue theater. “She was as she is now,” says Vickie Washington, her acting for TV and film teacher. Meaning: a bright light. “She has a presence. We talk about that a lot with acting. She is an actress who can engage literally all the way to the back of the house.” Upon meeting her you notice that the timbre of her voice and the quality of her laugh are rich and layered and so complex you want to keep hearing them.

“She’s fiercely intelligent,” Washington says. “She’s fiercely creative. Boldly creative. Bravely creative.” She remembers coaching Gary for the role of Cassandra in a monologue from Euripides’ The Trojan Women. The adjunct instructor taught a theatrical styles class, and Gary was adept at all of them—Greek, Elizabethan, Jacobian—but she excelled at the taut drama of Greek. Overall, she adhered to the notion of “valuing the craft, learning the craft, practicing the craft, sharing the craft” and had—and has—what Washington calls “a star quality.”

Washington remembers her, too, as being part of a cohort that vibrated with a rising Black activism. “There’s a circle of them that graduated at the same time who had a deep and abiding love, respect, and faith in our history and our heritage as African-ancestried people and understanding of the tenets of Sankofa: go back and fetch it so that you can use it to move forward.”

Harold Steward, a year ahead of Gary and a friend since they met in 2000, remembers her arrival. “The thing about her coming, it was kind of miraculous,” he says. The school projected only 10 new openings at each grade level after ninth, with perhaps only one or two spots for each concentration. A desegregation order further restricted the placements. Coming in a junior was almost impossible.

But once in, she quickly befriended a small band of students that would coalesce into an ensemble they called State of Emergency. Comprised of one other junior and three seniors, the collective would find each other in different parts of the school by hollering the group’s name (“I said, ‘State … of Emerrrrrrrgency!’”), which was a refrain from a poem they would perform together. It was, Steward says, “the way we called each other into being.”

Booker T. did not offer ensemble-based theatrical composition. “Nobody asked us to do this; we set our own parameters and found our own audiences,” Steward says of how State of Emergency organically “invented” devised theatre. Even with no manager booking gigs, they found themselves invited to perform at Paul Quinn College for the ambassador of Uganda over a weekend.

They were writing from a place of urgency. “This was early 2000s, so Neo-soul was on the rise,” Steward says. “We were idolizing Erykah Badu and the aesthetics of the Black liberation movement, the Black arts movement, and Blackness and the birth of cool and ownership of self and one’s African self.”

Gary, he remembers, came in with a “level of clarity” about “her presence in this world as a Black woman. She seemed to be quite clear,” he says, about wanting to understand theater and also her movements within a broader society. At 15 and 16, she was already reading Ntozake Shange (the playwright and poet best known for 1975’s for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf) and encountering Black feminist subjectivity.

“We were super militant young kids, learning about poetry, writing, literature, and how it could be used as a political breakthrough,” Gary tells me later. “We were cutting off our permed hair and wearing natural. [Badu] had this ‘pro’- rhetoric: this pro-Black, happy-to-be-Black accepting of yourself. So clinging to this heritage and aesthetic and way of being that felt firmly rooted in a Black acceptance, a Black love.”

There were tensions elsewhere. Gary was negotiating a relationship with her mother, Jocelyn Dunn, that she characterizes as “tumultuous.” At times, the rapport between the two strong personalities resembled tinder and flint.

If she could remember all those lines on stage, her mother pointed out, she could learn a Bible verse a day. When she was young, Gary and her brother attended Full Gospel Holy Temple, where the family had worshiped for several generations. “Ja’Tovia would come to school with Bible verses,” Steward says.

Additionally, “My mom wanted us to go to a certain type of school,” Gary says, and so the family—she and her brother, mother, and stepfather—moved from Oak Cliff to a house in Cedar Hill in the ’90s.

“It was a cute little three-bedroom moment,” Gary says, that sent her to school with White classmates, navigating dualities—“precarious terrain”—at home and school.

Perhaps for this and other reasons, theater came naturally. Performance, which she excelled at even in middle school, was a way to be fugitive and nimble. She had always been “a weird child” and creative, she tells me. She was always the one saying the thing that shouldn’t be said. But regardless, Washington says, “Her gift is kind of like rushing water: it’s going to find its way. She’s not going to be stopped.”

Moving to New York for college, Gary initially wrestled with disillusionment. The unhappy period brought obstacles, both race-based and aesthetic. She was unused to being radically limited in the roles she landed in theatrical arts. In high school at Booker T., a colorblind, progressive casting regime reigned: “My husband was Asian, my child was White,” she says. “It was like a little dream, a utopian space, where we were all upheld and earned the part based on merit.”

This was obviously not so in New York, where both at Marymount Manhattan College and in auditions, she was shuffled into race-based slots. You’re in the real world now, babe, she thought.

The move to filmmaking would ultimately be, in part, about reclaiming power, being the one behind the camera. In the meantime, the next several years flip by like a slideshow of Technicolor frames. Having decided to unenroll from Marymount, Gary traveled to the Caribbean and elsewhere, including South Africa, where a boyfriend was studying abroad; waited tables in SoHo while auditioning; and studied abroad herself in Accra, Ghana, after enrolling in a few classes at Borough of Manhattan Community College.

Ultimately, she knew her ambitions would only be served by returning to school, and so she chose Brooklyn College. Instead of theater, here she pursued both documentary film production and Africana studies, an all-encompassing, interdisciplinary major that combined feminist theory, literature, history, political science, cultural production, and media. Now fitted with an even more acute critical lens, “I’m learning about representations of Blackness in the early 20th century and how these archetypes came to be and how they persist,” she says. At the same time, as she auditioned for voiceover and television parts on the side, leading the life of a working Black actress, “I’m being told to zhuzh it up a little bit, make it a little more urban, make it a little more hood. So, intense meta-moment.”

Meanwhile, she landed postproduction and archival footage work for the filmmaker Shola Lynch, who was directing the extraordinarily dense, riveting feature documentary Free Angela and All Political Prisoners, and for Spike Lee, who was directing Bad 25, a documentary about the making of Michael Jackson’s Bad album that had Gary triaging footage of the megastar from his childhood to 1987. She spent time finding, organizing, identifying, and indexing archival footage, doing the “grunt work.” The Angela Davis documentary in particular was “a dream come true.” She delved into courtroom documents, audio and visual sources, and prison letters between Davis and George Jackson and other luminaries who were part of the Black Power period. “So it was a political education crash course as well as a film production module,” she says. “It was wild. Wild.”

By the time Gary enrolled in an M.F.A. program in social documentary filmmaking at the famous School of Visual Arts in Chelsea, her skill set and knowledge base were formidable. But she remembers the school pushing her toward direct cinema, the observational, journalistic, fly-on-the-wall style of documentary.

“They were like, ‘This is what’s in right now. We want you to have jobs,’ ” she says. “I couldn’t care less about a job. I had already worked for Spike Lee. I knew I wanted to be the Spike Lee. I wanted to be the Shola Lynch.”

If Gary was iconoclastic, she found a fellow outsider and rebel in directing professor Michel Negroponte. In his courses, she says she was “gravitating toward the nontraditional work.”

He showed work by the great American documentary filmmakers of the ’60s but also the “weird stuff” within nonfiction. Stan Brakhage’s Mothlight (1963), in which the translucent wings of moths glued to the filmstock filter light. Jay Rosenblatt’s Phantom Limb (2005), wherein he spliced his family’s Super 8 home movies together with archival footage in a poignant autobiography.

Gary would also add to Negroponte’s syllabus her own roster that was non-male and non-White: Cauleen Smith, Trinh T. Minh-ha, Julie Dash, Kathleen Collins. Steve Cossman at the film nonprofit Mono No Aware in Brooklyn showed her Len Lye’s A Colour Box (1935), a three-minute riot of color shot on 35mm film that Lye had scratched, painted, and punched holes in. She found Paul Sharits’ “flicker” films of the 1960s, aggressive, avant-garde, rapid-cut sensory bombardments, with shots scarcely longer than two frames each. A lightbulb flashed in Gary’s head.

She was learning film could be nonlinear, abstract, the kind of experimental storytelling that was closer to poetry. The filmmakers she was gravitating toward dismissed, sometimes brutally, the idea that one should shoot and roll film forward at 24 frames per second.

Gary took all of this in—her experiences with Lynch and Lee and Negroponte and others; her own exploration and study; her own self—and emerged as a one-of-one.

“Starting in the documentary world and ending up with Paula Cooper—that’s pretty special,” Negroponte says, chuckling. “I’ve taught in many programs, and, no, that’s not the world that most people end up in.”

When I visit Gary’s loft near downtown, she has been burning frankincense. “I do want to ask that you not photograph any of the altars,” she says after welcoming me, and her tone is clear but light. “I’m very woo-woo-woo.” Then: “You haven’t picked up on that?” She laughs.

But, of course, I have. When we first spoke over Zoom last November, she paused at one point in our conversation and disappeared beneath the table, reemerging with something in her hand. “I dropped something I need to hold onto,” she said. It was a small black stone.

I take in the altars in various parts of the loft. They’re dedicated to the West African orishas Yemonja and Elegba, the Yoruba warrior protector spirits, as well as Gary’s ancestors. Like Toni Morrison and Alice Walker, she engages in ancestral veneration and spiritual work, she says, naming inspirations and compatriots.

“My spiritual head is Yemonja,” she says. “She presides over the ocean, and it’s said she has as many children as fish in the sea. She is associated with fertility, fecundity, wealth, creativity. Think of the vastness of water. Think of the essential nature and necessity of water. That is Yemonja. All the things associated with the beauty of motherhood and the protection of children and women. This is Yemonja.”

She continues, “It requires labor,” referring to the indigenous spiritual practice. “It’s making space in your life. You need to honor them, making literal space, like altars. You include them in your life, and you’re in conversation with them. They guide you.” As a result, she feels secure, that she is not “putting ridiculousness out into the world.” But also, “That’s why I feel like what I’m doing is something they want me to do, is something they’re encouraging, is something they’re opening the road for, guiding.” (She had told me over Zoom, “It really does feel like I’m in here with a bunch of ghosts. Because I am, low-key.”)

Leading me to her worktable, which faces the Trinity River, she points out the light pad she uses for direct animation onto 16mm film stock and guides me through her technique. She pulls out film strips with orange petals pressed onto the surface; cotton swabs and old toothbrushes she uses to spatter paint; India ink and X-Acto knives that turn transparent strips into constellations of dots or etch lines around figures or objects, frame by frame.

“It allows the film to feel like it’s alive,” she says.

Perhaps the best example of her style—and certainly the most well-known—is 2019’s The Giverny Document, which The New Yorker deemed “rhapsodic.” The Giverny Document is a 42-minute single-channel film collected from many sources: there is footage of Claude Monet’s orchard at Giverny, where Gary completed a residency, and shots of her interviewing Black female passers-by in Harlem, asking if they feel safe in their bodies, on the street, in the world. There is Nina Simone transforming Morris Albert’s “Feelings” at the Montreux Jazz Festival in Switzerland in 1976. And there are clips from the in situ video filmed by Diamond Reynolds of her boyfriend Philando Castile, killed by a Minneapolis police officer in 2016. Gary says the film, which has won numerous awards, is a comment on “bodily autonomy, Black women’s bodies as spaces of commodified production, the period of enlightenment and industrialization and colonialism all coming together.”

This twining of strands she connects to Black expressions of religious and musical tradition. A conversation about her practice reveals the ways it overlaps with jazz, blues, gospel, hip-hop. “I come from a bunch of Black preachers on both sides, like Black Southern Pentecostals,” she says. “So music and storytelling permeate the entire experience.”

You can see how she interpolates and extrapolates—like a jazz singer riffing or a DJ flipping a sample—in An Ecstatic Experience, the six-minute film she premiered on the festival circuit in 2015. Jittery and profound, it’s based around a scene from a 1965 television show, interspersed with other footage. Hand-etched lines encircle the actor Ruby Dee’s face in a halo and morph with every frame, the lines seeming to crackle with electricity. No film theory is necessary: you are turned inside out, utterly undone. It’s a solemn testament to resistance and liberation.

An Ecstatic Experience was the first film of hers to garner notice by gallerists. Frank Elbaz had been seeking just such an artist for his gallery, bridging the worlds of art and cinema, and marveled at the way Gary manipulated film. She wasn’t an artist who made video work but a filmmaker who treated film, potently, as pictorial art. “She brings it back to drawing,” he says.

In 2018, at Art Basel Miami, Elbaz showed An Ecstatic Experience to Steven Henry, director of Paula Cooper’s gallery in Chelsea, introducing her as an artist to watch. Even on a small monitor amid the melee, “It truly stood out in the cacophony of visual material,” Henry says. “I was like, ‘Wow, this is extraordinary.’ The way she approaches film as a kind of filmic collage felt very fresh. She’s always pushing.”

Once back in New York, Henry urged Cooper herself to visit neighboring gallery David Zwirner, where An Ecstatic Experience was being shown as part of a group exhibition on James Baldwin, curated by the Pulitzer-winning writer and critic Hilton Als. The stars were aligning.

As a result, in both 2019 and 2020, Gary had solo exhibitions with Elbaz and Cooper, where she showed The Giverny Document as The Giverny Suite, a three-channel installation to which, in a return to her theater-kid brio, she added a 19th-century French settee—and, in the Cooper show, altars in the corners. “I’m resisting categorization,” she says. “I’m attempting to put forward my own style, something that is new, a new language.”

Versions of Suite have been acquired by the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, the National Gallery, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Block Museum at Northwestern University. (The three-channel installations with their accompanying sculptural elements, the settee and altars, can circulate in different ways from the films.) She is determined to continue to “occupy space in an installation context, because the work takes on new life,” she says.

“Movement and touch and light come into play in ways that the film experience does not afford us.”

The memoir, though, is different from all of this. The Evidence of Things Not Seen—a title she drew from Hebrews, but that has broad resonance—is long, and its crafting has been arduous. The film has had her delving into memory—her own and others’—and deep wounds, and she’s in it more than any of her other work. “Intense shit,” Gary says.

The project began as the short film Deconstructing Your Mother, created while she was an undergraduate in 2011. By 2014, she was awarded a Sundance grant (the first of many), which is when she says it really began. But by 2017, the layers of what she now realized was an autobiography had become so emotionally charged that she could scarcely bear to pull up the files on her hard drive and listen to what was being said by herself, her parents.

What happened in between: she received Super 8 footage of family gatherings shot by her great aunt, who fetched the reels from her garage. She’d widened the scope, poked and elicited confessions and confrontations. In building her kaleidoscopic patchwork, with its far more subtle nuances of collaboration and authorship, point of view and ethics, her own footage from earlier years became archival material, incorporated. She had staged therapy sessions to record herself speaking of the patterns she was unveiling, the slippages of memory.

Other details surfaced from her brother, her father, aunts, uncles, cousins, grandparents, her teenage boyfriends. The film morphed on her, flipped the camera around: her disembodied voice became flesh and blood, discussing, as she says, “the blood that runs through [our] veins.” She dug up generational strata: power dynamics and “long lines of divorce or abuse or addiction and alcoholism.” It is “this very deep investigation and excavation of my most intimate relationships, my family history, and myself.”

Gary got to a place two years ago where she decided, This is gonna take as long as it’s gonna take. “I was trying to rush and push through because I had won these grants and there was a lot of momentum,” she says. “And this is not that type of project. And once I realized that, things became more tenable for me.”

And so, late last year, even when the FOMO of being far from Brooklyn’s blur of openings tempted her, she stayed in Dallas. This piece, which she hopes will find broader distribution and be “in everybody’s living room,” this piece which will be her at her longest and most vulnerable had to unfold as life unfolds. That’s why she does Pilates four times a week and consciously takes care of her body. It’s why she takes breaks. Why she’s decided it’s OK to slow down. To take 10 years.

But now it is starting to peek out, at least a little. “I KNOW IT WAS THE BLOOD,” Gary’s current solo show at the DMA, offers the only teaser of the memoir feature there is. Screens show excerpts of interviews, the raw material for Evidence. One image, which opens the show, is of Gary’s mother pregnant with her brother Jamael.

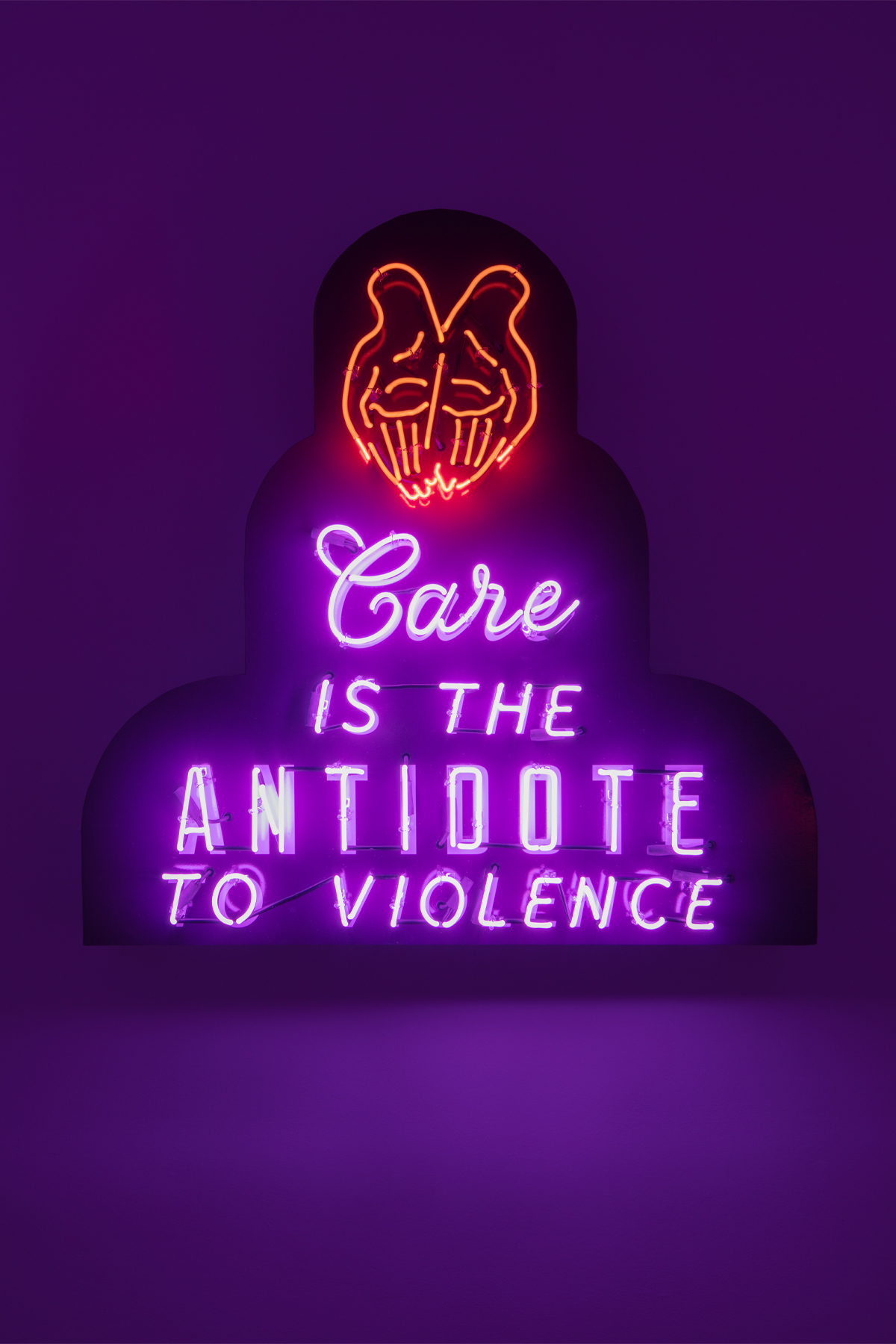

The commissioned work at the heart of the exhibition is a 12-foot armillary sphere with rotating steel rings, covered in cotton, which brushes the limit of what can be displayed in the museum’s spaces (outside the 45-foot-high barrel vault). The piece, titled In my mother’s house there are many, many …, is now in the DMA’s permanent collection. Accompanying the commission are works that relate to the feature film in their evocation of her family’s multigenerational story. A painting incorporates a phototransfer of her father or, in Mama’s Babies, of her, her mother and brother at the State Fair. The paintings’ frames are deconstructed and decked with neon. (This is the first time she has exhibited her painting in earnest, she says.)

“It’s tested the ways we usually work,” says Katherine Brodbeck, Hoffman Family senior curator of contemporary art at the DMA. We sat over coffee a little more than one month before the exhibition opened. Just a week earlier, the DMA had to send the exhibition brochure to the printer missing details such as the exact duration of a film clip. But that’s precisely what’s exhilarating about working with a contemporary artist, when the work at the center is still in motion. When the artist at the center is still in motion.

To Gary, the DMA show and the memoir feature itself are just part of her many reinventions, her mercurial changes, which are happening in real time, expanding the work. And there are more to come. She would love to write a romantic screenplay, move into other markets, be “seen in everybody’s living room.”

For now, we are in hers.

“This is where I edit,” she tells me when she lets me enter a space I had missed when I first entered her studio loft. “Computer. All the hard drives. Digital material. Various notebooks. More woo-woo-woo.” She gestures around. “My great-grandmother looking on, Laura Anne,” she says, pointing to a photograph on the wall. “Like, ‘Girl, what you doin’? You better do it right.’ ”

In our conversation leading up to my visit, I had been nervous. Who was I to enter her private world?

But at her loft, I am treated to something of a personal installation experience. Together, we watch her latest film, Quiet As It’s Kept, which was the centerpiece of the show in February and March at Paula Cooper. It is what she calls her “contemporary cinematic response” to Toni Morrison’s novel The Bluest Eye.

She sits on a stool; I sit at her desk. I am only missing the crowd in the gallery, missing only the shimmering silver corset she wore to the opening, her hair cropped and bleached a moon-like white. About 15 minutes before, she had been showing me vintage 16mm commercial reels she buys on eBay, at estate sales, or in libraries. Like an haute couture seamstress misthreading a sewing machine she hasn’t used in a while, she shredded the strip’s leader on her vintage Eiki projector. In the ’70s commercial for Reveal see-through roasting wrap, a Black housewife smiles. She awaits Gary’s animations.

Now this. Neon blue. Orange marigolds. Archival footage of Shirley Temple. Toni Morrison and Lukumi priest and scholar Dr. Kokahvah Zauditu-Selassie (whom she calls Mama Koko) as talking heads. A wash of animations dense with symbolism, the blue eye of Morrison’s novel like a protective amulet.

After the first two minutes, I wanted to lie down and simply think. To make film in this way is an act of devotion.

This story originally appeared in the September issue of D Magazine with the headline, “The Prodigal Daughter.” Write to [email protected].

Author

Eve Hill-Agnus

View Profile

Eve Hill-Agnus was D Magazine’s dining critic from 2014-2021. She has roots in France and California and during her time at D wrote…