“It began,” he continued, “in a little town in Missouri …”

If it sounded a bit familiar, it was probably because Morrison had already showcased this twisting saga of coldblooded betrayal at least four times on “Dateline” broadcasts over the years. But there was also that voice of his, a rhythmic and balmy baritone that sounds like home for a generation of murder-mystery connoisseurs — all the more so, perhaps, now that it’s coming to them straight through their ear buds.

Nearly 32 years after its TV debut, the once-dusty “Dateline” brand has found a massive new audience through podcasting that has helped it climb back to the top of a booming true-crime market it first conquered in the O.J. era.

With more than 1.3 billion downloads since 2019, “Dateline” continually ranks near the top of the major podcast charts. Apple ranked it as the No. 3 podcast across all genres for the second straight year — mentioned in the same breath as powerhouses like “This American Life” and Barstool Sports’ “Pardon My Take.” It was Podtrac’s No. 1 true-crime podcast of 2023, when the Alex Murdaugh trial in South Carolina whetted a public appetite for crime-scene reconstructions and courtroom drama.

“We’ve got the biggest name in true crime, and there are definitely a lot of pretenders to the throne,” said Josh Mankiewicz, a longtime “Dateline” correspondent and former podcasting skeptic.

The true-crime genre helped set the pace for podcasting’s growth over the past decade, ever since “Serial,” a reinvestigation into the 1999 murder of a Baltimore teenager, became the first podcast to pass 5 million downloads. Hundreds of imitators followed, many boasting edgy storylines, diverse young talent and sleek audio effects.

Yet “Dateline” is beating them all, despite relying on narrative tropes from 1990s network television and correspondents of similar vintage. The “Dateline” podcast empire has grown to hundreds of hours of content, from richly produced narrative serials to raw audiocasts of the latest TV episodes to behind-the-scenes chatfests with its reporters and producers.

This week, NBC will unveil “Dateline Originals,” a new podcast hub collecting all of “Dateline’s” addictive narrative series into a single feed, so fans can stream them seamlessly, like an IV drip of tragedy. These include multipart stories such as “Mommy Doomsday” (the Idaho mother who killed her two children in an apocalyptic fervor), “Murder & Magnolias” (a Charleston banker’s botched attempt to have his wife killed), and “Motive for Murder” (the mysterious link between two young people gunned down in Houston).

Which prompts the question: Why the hunger for all this horror and heartbreak?

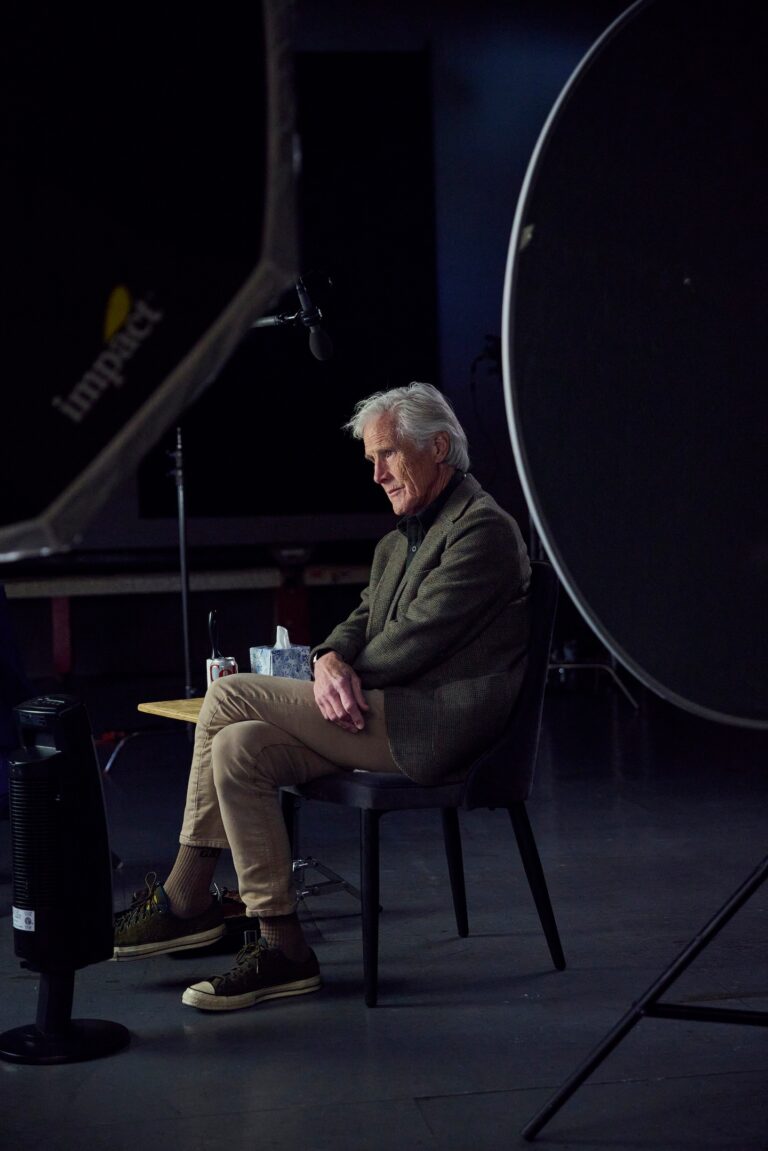

“It’s a question I grapple with a lot myself,” Morrison said during a recent interview. “Why do people care about this so much?”

Then he paused, in that perfectly calibrated Keith Morrison way, before answering his own question:

“These are stories about people and what they do for each other, and to each other, and what makes them tick,” he said. “Some of us do things that are dreadful. And you have to know why and how it’s possible to do anything like that.”

Long before “Dateline” was namechecked as Taylor Swift’s favorite show, or spoofed on “Saturday Night Live” with Bill Hader as a gleefully morbid Morrison chomping popcorn through a grisly interview, it was just another “60 Minutes” wannabe.

The 1970s and 1980s were big years for TV newsmagazines, but NBC could never get one to take flight like CBS’s groundbreaking investigative show or ABC’s “20/20.” Then in 1992, something clicked. “Dateline” debuted with hosts Jane Pauley and Stone Phillips, an immediate success.

Initially, it offered the standard buffet of stories — investigating Capitol Hill corruption in one segment, sharing a heartwarming tale about children thriving in the face of disabilities in another. In 1993, the show fired three top producers for staging a fiery collision shown in a story about the safety of GM trucks. But “Dateline” was a hit, eventually airing as often as five nights a week.

And by the late 1990s, it had found its groove in true crime. Liz Cole, a former NBC page who joined the show on loan as a guest booker in 1993, recalled the audience response for coverage of the O.J. Simpson murder trial and the mystery surrounding the 1996 killing of child beauty queen JonBenét Ramsey. Quickly, the story buffets were replaced by crime sagas that filled the entire hour.

“We did really make that pivot before true crime became this huge thing,” said Cole, who eventually rose to executive producer of “Dateline” and president of NBC News Studios. “When everyone was on Netflix watching ‘Making a Murderer,’ we had already been doing it for years.”

Cole and others at the show credit David Corvo, who joined NBC in 1995 as a vice president overseeing prime-time news programming, for nudging “Dateline” into true crime.

Corvo stepped down at the end of the year from his role as senior executive producer, a job that Cole has now inherited. He in turn credits Cole for the show’s success, saying she had the inherent understanding of how stories about even the most heinous acts needed to have heart.

“People can relate to the stresses of life: the betrayals, the broken opportunities, the sadness you go through, the anger,” he said while packing up his office overlooking the Rockefeller Center ice-skating rink in December. “It’s underlined in ink by the extreme level somebody takes it to. But if you don’t understand what leads up to the crime — if we don’t understand the chaos and the catastrophe that leads up to the crime — then it’s not a good story.”

“Dateline” is now NBC’s longest-running prime-time show, and Corvo and Cole’s shared sensibilities over a long-term partnership clearly brought a reassuring consistency to the product. “People know what they’re getting,” said Mankiewicz.

“One of our senior producers would say to us, ‘When you look at stories, you guys never really disagree,’” Corvo said. “We’re just naturally on the same page.”

The two agreed about something else: The brand needed to grow.

In late 2018, they pitched the staff on podcasts. Some were resistant.

Mankiewicz, 68, joined “Dateline” in 1995 as it made its pivot to true crime but said he never really understood the public’s appetite for it until he covered the Jodi Arias murder trial in Phoenix in 2013. There, standing in a line of people waiting for courtroom seats that stretched down the block, he met two women who had taken vacation from their insurance jobs in Minneapolis to be there.

“That’s when I thought to myself, ‘You’ve been missing something here,’” he recalled.

Even so, he had only rarely listened to podcasts himself and, like others on the team, didn’t quite get the appeal.

“I said, ‘We do television. Why in heaven’s name would we do audio-only, as they do in old-fashioned radio?’” recalled Morrison, 76. “But boy, was I wrong.”

It wasn’t easy at first for a network television team to turn their material into audio stories. The pacing is different in podcasts: “Dateline” the TV show might be able to pack an entire homicide trajectory, from motive to sentencing, within a one-hour block; but audio audiences had developed a taste for more leisurely story arcs, broken into chapters the length of a morning jog. And producers had to learn how to tell a tale without relying on visuals.

Initially, “Dateline” hired outside consultants to transform their television work into podcasts. But “we soon realized that we were better off doing it since we really knew the voice of the show,” Corvo said. Before long, the only major challenge was simply making the time for the team to tackle podcasts in addition to their TV obligations. (The weekly “Dateline” broadcast remains a priority, and there’s been a surge of viewership for new and old episodes on NBC’s Peacock streaming service.) Meanwhile, “the correspondents really liked doing it,” he said.

“Dateline” came to the crowded true-crime market with an asset even bigger than its name: its massive archive.

It takes a lot of reporting to pull together the elements of a compelling narrative. Not every podcast team has the time or skill to do that kind of reporting. And in the rush to feed a growing audience, some podcasts have come across as weak regurgitations of Wikipedia synopses. Others have been accused of borrowing too freely from the original work of book authors or local news reporters.

But “Dateline NBC” never had to scrape for material. Some of its most successful podcasts have been built upon original reporting that its producers and correspondents had been stockpiling for years. Morrison’s most recent podcast series, “Murder in Apt. 12,” told the story of an Arkansas college student found slain in her apartment in 2005 — a case “Dateline” probed for television in 2008 and 2013. “Mortal Sin,” a Mankiewicz series released last month, centered on the web of sex, murder and deception revealed after the death of a pastor’s wife, a story he first covered in 2010.

The Pamela Hupp story — which only grew more complex after NBC first reported on it in 2014, as Hupp was accused of additional crimes — was “Dateline’s” first podcast, and a natural fit for the new medium. Morrison and his producers broke it into six half-hour episodes. When she listened to the first episode of “The Thing About Pam” on the subway, Cole knew they had a hit.

“I could just hear it,” she said. “It was so wonderful having Keith in my ear like that telling me a story.”

The series — including a 12-minute “bonus” episode after Hupp was hit with new charges in 2021 — has been downloaded more than 32 million times since its 2019 release.

It launched “Dateline” into the podcasting stratosphere, with an audience skewing much younger than its broadcast fan base, many of whom may never have watched the TV show. At a true-crime convention, Corvo watched as devotees thronged a hotel ballroom, standing in line for a chance to take photos with his correspondents.

“They were like the Beatles,” he said. “We had to escape through the kitchen.”

The distinctive voices of its correspondents is another important factor that has helped separate “Dateline” from competitors, Cole and Corvo say. Even if those correspondents don’t love the sound of it themselves.

“I find it very uncomfortable, honestly,” Morrison said through a warm, mossy chuckle. “I listen to myself when I have to.”

Mankiewicz recalled how his old bosses at ABC tried to get him to work on what he calls his “unpleasant nasal voice.” With his unexpected success in podcasting, which now takes up about 75 percent of his time, he’s glad the lessons from a vocal coach never stuck.

“This voice is here to stay,” he said.

The “Dateline” team anticipates a seamless transition from Corvo to Cole, with a veteran show producer, Paul Ryan, stepping up into her old job. Yet many have begun to entertain a nagging question: When will the audience get tired of true crime?

Morrison, for one, wasn’t venturing an answer. In early December, though, he sat down to record a program that represented something of a departure from his usual work — though still, his producers hoped, just as addictive for his audience.

It was the tale, he said, of a man he called “the meanest Christmas villain of all time.”

“Oh yes, he’s the O.G. of bad guys, all right,” Morrison said, in his usual rich cadences. “Darth Vader, the Grinch, Voldemort all rolled into one evil lump of a man.”

Here, for the second season of “Morrison Mysteries,” yet another “Dateline” spinoff, Morrison was retelling the story of Ebenezer Scrooge — who “counts his money while children starve, who mocks the sick and begrudges his most loyal friends even the tiniest bit of happiness.”

Still, Morrison promised his listeners that Charles Dickens’s 180-year-old “A Christmas Carol” would resolve itself in perfect “Dateline” style: “This nasty piece of work will get his comeuppance — and in the most unexpected and satisfying way.”

Morrison told The Post he has no plan to stop telling stories — at least not until NBC “lets me know my sell-by date.” He went on.

“Stories are like children — you don’t want to have a favorite,” he said. “Each one feels like the best one you ever did, and it’s the worst one you ever did if you’re having trouble putting it altogether.

“But later on, you think, ‘Boy, this is the best one ever.”