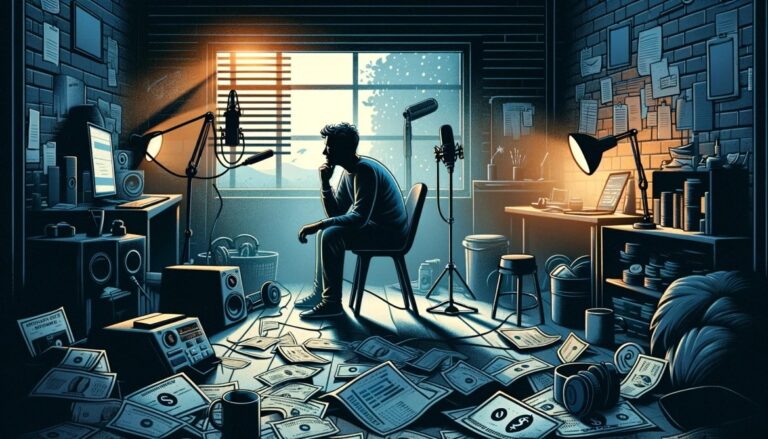

The CPM model of advertising does not and will not work to sustain podcasting.

When I worked as Head of Content at Pushkin Industries, I never made it my job to truly understand how the CPM model worked. I had my hands full managing all the shows and staff, and we had talented people handling marketing and sales. So I left the job to them.

I've certainly heard some complaints about it. Too many shows to sell at once, not enough revenue, bad partnerships, endless misunderstandings and frustrations. At the time, I was staying out of the weeds. But now, as I focus on a new vision for funding audio storytelling, I need to understand what exactly is wrong with the current model.

So I did a little research.

Let's start with the basics. What is CPM? I found this simple definition in an online advertising guide.

M stands for “Mille”, or roman numeral 1,000. Also, since most people only listen to a podcast once, impressions are essentially the same as downloads.

CPM was first introduced in 1995 to set advertising rates for online banner ads. For static websites, it was a convenient and unbiased way to determine the value of an advertising campaign. And it has become the standard for all digital advertising content.

There are three basic opportunities to promote your podcast episode:

- Before the show (pre-roll)

- In the middle of the show (mid-roll)

- After the show (post-roll)

However, these three methods are not created equal. Pre-roll and mid-roll spots are considered the most valuable. Because who would listen to the credits of a show all the way through, including the ads that follow? And there are limits to how many ads can run while maintaining the integrity of the listening experience. Too many ads spoil the atmosphere. In my experience, a good rule of thumb is one pre-roll, two mid-rolls, and one post-roll.

In the early days of podcasting, advertisers quickly learned that hosted lead ads were most effective. This is when the podcast's trusted narrator shares first-hand experience with the product or service they're promoting and tries to sound as authentic as possible. serialMailchimp ads are a prime example of this.

There are all sorts of ethical concerns here. The whole idea of ”advertising music” arose when listeners were confused about the difference between program content and advertising content. (Gimlet created this handy guide at the time.)

Additionally, these ads, especially the more appealing ones, take a lot of time to write, record, and produce, taking up valuable programming time and increasing overall production costs.

How is CPM evaluated?

According to Acast, the largest podcast ad sales company, average CPM rates for podcasts range from $15 for a pre-recorded 60-second spot to $40 for a host-read ad.

Since CPM rates are based on impressions/downloads and new shows don't have known download numbers, CPM rates are usually based on an estimate of a show's performance. If the show goes well, everyone wins. However, if a program does not perform well at the box office, the company that sold the advertisement must provide so-called make-up, offering slots in other related programs to fill the gap. It's not a good situation for anyone.

Let's be generous and say the show runs four ads for the host to read for a $40 fee.

That's $160 for every 1,000 impressions.

In my last essay, I talked about fair rates for creators of various experience levels. The survey respondent determined that $60,000 is a good base annual salary for an entry-level producer. That means the show would need to be downloaded 375,000 times a year to pay her one producer's salary with CPM-based ad revenue.

I also argued that the annual cost of a highly produced 10-part narrative show, produced by a top-notch team, amounts to approximately $500,000.

A show like this would need more than 3 million downloads in a year to break even.

Of course, some shows get more downloads than that. It is usually an “always on'' program. However, according to the 2023 Podcast Marketing Trends Report, the majority of podcasts earn far less, even if they are of high quality.

Other factors are also involved

Some podcasts can secure higher CPM numbers by having longer ads read by the host or by using high-profile talent. But these high-profile talent usually have some sort of revenue-sharing agreement, so any extra money they make likely won't contribute to their bottom line, much less trickle down to the production team.

Some advertisers are interested in reaching niche audiences on specific subjects and will pay a premium for that access. Also, some event-related and other timely programs have higher viewer ratings. Additionally, you can bundle a large number of shows and sell advertising across an entire network or set of shows, rather than selling them individually. This is how most existing networks do it, and it's the best way to guarantee the scale and reach that most advertisers are looking for.

But that means each show and creator gets an even smaller piece of the pie. Plus, podcast ads are easy to skip. Advertisers avoid controversial or overly sensitive podcast content. And many shows don't have any ads at all.

There's another complicating factor here. When Apple released its iOS 17 operating system at the end of his 2023, the number of downloads decreased across the board. This was a carefully considered change on Apple's part to ensure more accurate download reporting. But there are other examples where creators of programs large and small experience unexplained changes in download numbers. There are undoubtedly countless ways to exploit the system, including suspensions, hacks, and bots. Guidelines set by the Interactive Advertising Bureau attempt to bring some order to the download chaos.

But the bottom line is that a system that relies on download numbers to determine a podcast's value is unreliable, unfair, and unsustainable.

CPM models don't work for podcasts.

What about sponsorship?

There is another way to secure advertising dollars for your podcast: sponsorship. That's when an advertiser supports an entire program or series of programs, and more broadly associates the advertiser's name or brand with the content. This is usually done through promotional spots at the beginning or end of the show. And it is most often heard on public radio in the form of underwriting.

In fact, public radio stations are not allowed to use host read ads. It is considered a conflict of interest and unethical for reporters to speak on behalf of the products or services that fund their programming. Instead, the ad (or underwriting spot) is read by a neutral voice with a clear distinction between the two.

Unlike CPM, underwriting rates are flexible and based on the viewer's perceived value. So how do you figure it out?

Public radio primarily uses Nielsen ratings to determine who listens to what and for how long. Nielsen's history is long and interesting, and you can read it here. But most importantly for our purposes, the metrics are based on real human behavior. Nielsen places hardware in people's homes to track viewers and viewers. They ask people to keep a daily diary that records their media habits. And since 1987, “People Meters” (now wearables) have been introduced to track listener behavior as accurately as possible.

Until recently, Nielsen couldn't track headphone listening. But they are constantly evolving, and actual human behavior remains at the center of the equation.

Salespeople use these Nielsen ratings, along with many other metrics, to go to market and convince advertisers that their station's programming will reach listeners who will buy their brand. And then convince brands to pay a premium to reach those audiences.

I would argue that fees are nuanced and specific, which is a much better way to go about pricing.

But as far as I know, even the best-funded radio stations are unable to bundle broadcast and podcast services during underwriting sales, leaving podcasts reliant on a broken CPM model. And even with the underwriting option, public radio stations are not immune to last year's turmoil and mass layoffs.

What should I do then?

Whether you're listening on a podcast app or over the air, the quality content is essentially the same: a combination of reported narratives, interviews, and chat shows. Nearly all broadcasters offer their broadcast content through online streaming services and other apps, and more and more podcasts are signing broadcast deals to distribute their content through terrestrial radio.

If you listen to the same content, shouldn't you pay the same amount?

Shouldn’t there be a way to combine the human-centered, nuanced approach of radio underwriting with the high-volume, purely quantitative models of CPM?

Building on my idea of a co-op-run network where creators can make a sustainable living and their shows are monetized through grassroots sales power.

- What if the network included “podcast stations” that operated like radio stations, but with more content and less overhead?

- What if we moved away from CPM models and instead used human-generated metrics to determine the value of an audience listening to a podcast?

- What if the salesperson is a true fan of the content they’re selling and is probably reading the ad spot itself?

- And what if the salesperson not only sells advertising and underwriting spots, but also memberships? Sales is sales, right? There's something for everyone.

I've been exploring these ideas with Kristen Hayford, a veteran marketing expert who tests some of these theories on “The Kids Should See This.” The membership-based website offers carefully selected educational content for kids and helps parents “avoid the 'wild west' of the YouTube algorithm.” I will keep a close eye on her work.

For now, I'll leave you with this good news.

A large amount of advertising money is being invested. Let's think about how to distribute them differently.

Mia Lobel is a veteran audio producer, manager, educator, and founder of Freelance Café, a long-running community group that is now a networking resource for independents in public media in the form of Substack. Drawing on his experience as a former head of content at Pushkin Industries, he currently works as a mentor and consultant, helping individuals and companies build great teams, set up sustainable production processes, and create impactful, entertaining and memorable products. We help you create content that stays with you.