Joe Minicozzi is a Harvard-trained urban planner from Asheville, North Carolina. The readers of Planetizen, a respected outlet that covers planning, voted him one of the 100 most influential urbanists of all time, placing him at No. 33. He’s clever and professorial, a slightly younger, hipper Paul Giamatti, with a full goatee and a bald head. Using data from local sources, he travels the country, trying to show cities how to avoid financial ruin. His PowerPoint presentations tend to galvanize some people and make others squirm.

Minicozzi’s firm, Urban3, looks at the taxable value of land 1 acre at a time, showing how zoning and land use drive cities’ revenue. He explains it this way: you wouldn’t ask how many miles a car travels on a tank of gas. You want to know how far it can get on a gallon. Similarly, a Walmart might represent a lot of taxable value, but it also occupies a lot of land. In Dallas County, Minicozzi found that a Walmart represents, on average, just $600,000 in taxable value per acre. That’s because all those parking spaces aren’t worth much, and the building itself is designed to last only about 15 years. It’s a smart strategy to keep taxes low. Good for Walmart; bad for city coffers.

In January, Minicozzi Zoomed into a committee meeting of the Dallas City Council to present some of the findings from a study he’d conducted on Dallas County. Council Member Cara Mendelsohn, who represents Far North Dallas, seemed to squirm the most. She didn’t like that Minicozzi was “denigrating a Walmart.” People like Walmarts, she said. “We should have the full array both of housing and retail and even density,” she said. “When a Walmart closes in Dallas, we get emails saying, ‘Where am I going to shop?’ ”

“Don’t get in the way of information. You can interpret it any way you want, but let’s all look at it together.”

Joe Minicozzi

I called Minicozzi after his exchange with Mendelsohn. Her reaction, he says, isn’t uncommon; some people are naturally defensive of the status quo. His response is: “Don’t get in the way of information. You can interpret it any way you want, but let’s all look at it together. And then you can come to your conclusion.” He just wants cities to think about where the Walmart should go and weigh the opportunity costs of allowing so many similar big-box stores. By the same token, you can think of single-family lots as the Walmarts of housing.

Right now in Dallas, there are some folks in single-family neighborhoods who are stoking anxiety over a possible change in zoning. Planners at City Hall are researching how to encourage more housing construction through a variety of methods, including allowing duplexes, triplexes, and quadplexes in neighborhoods currently filled with only single-family homes. That possible change has some people scared, and they’re letting councilmembers—like Mendelsohn—know it.

So Minicozzi came to town at a good time, like an urbanist Paul Revere. Let’s consider what he found.

For Minicozzi’s study of Dallas County real estate, we can thank the MetroTex Association of Realtors. That’s the group that actually hired him. Handing over the data he needed to do his work presented a challenge, though. Texas is a “non-disclosure state,” one of 12 in the country that doesn’t require property sales figures to be public. If a property changes hands in Dallas County, only the buyer and the seller—and the multiple listing service, which members of MetroTex and other similar Realtor groups across the region have access to—know the actual price. Not even the Dallas Central Appraisal District gets access to this information.

So MetroTex, working with the Texas A&M Real Estate Center, came up with a novel solution. They handed over the proprietary data from the MLS so Minicozzi could judge whether the appraisal district taxes properties fairly. (Short answer: DCAD generally does a good job. Although less expensive properties were more often overtaxed than more expensive homes, which were more commonly undertaxed.)

As part of this research, Minicozzi was also able to determine the average taxable value per acre for both residential and commercial land uses in the county. This is the first time a study like this has ever been conducted in Texas.

“We’re Texans. We want to protect our non-disclosure privileges,” says Gerald Klassen, a research data scientist at the Texas A&M Real Estate Center. “But we struggle with knowing the fairness of the assessment process, so this was the first time we were able to evaluate the fairness of it over time.”

Which brings us back to the auspicious timing of this study. Right now at Dallas City Hall, planners are analyzing all the land uses—the zoning—across Dallas, conducting public meetings and assessing what should be built where and how. They are updating a nearly 20-year-old comprehensive land use plan called ForwardDallas, which will in turn guide future zoning decisions. This process was the magnet that has agglomerated longtime single-family homeowners to the City Council chambers like a box of paper clips.

But if you take the emotion out of it and just look at the math, the way forward seems clear. What gets built gets taxed. The city runs on that revenue. And right now, we need more of it. During the current fiscal year, the city anticipates generating about $1.44 billion in property tax revenue, 61 percent of which is immediately diverted to public safety. That property tax revenue equaled a little less than one-third of the city’s $3.6 billion operating budget. New properties will add a little under $28 million to the tax rolls this year.

In May, the city will vote on a $1.25 billion bond program. That’s money the city needs to borrow to keep our affairs in order. Ideally, the city would borrow money only to build new projects that would generate a return. We borrow to fix what we already have; the city of Dallas maintains no reserve fund to pay for maintaining its infrastructure.

During the discussion over bond allocations this winter, city staff said that we have $17 billion worth of “unmet needs” that the bond will fall woefully short of addressing. And those needs keep growing. In 2021, for instance, 48 percent of all city-owned infrastructure managed by the Transportation Department was at least 40 years old. According to city data, it costs an average of $550,000 to replace old traffic lights at a single intersection. The city of Dallas says it has 11,790 paved lane-miles of traffic lanes to maintain. It costs about $720,000 to resurface 1 mile of a single lane. It costs anywhere from $2.1 million to $3.7 million to fully reconstruct that same mile of road. The cost of asphalt jumped 30 percent between 2021 and 2022, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (Fun fact: most cities, including Dallas, account for roads on their books as an asset, not a liability, which is patently insane.) Minicozzi insists that residents need to know the dollar amount of maintaining all this infrastructure, and policymakers need to do the math and determine how to pay for it all.

Beyond infrastructure, the city has a lot of employees to take care of. Dallas has a pension for city workers and another for cops and firefighters. They are cumulatively underwater to the tune of about $4 billion. We will either have to slash benefits (which will make hiring and retaining people more difficult), or we’ll have to borrow even more money to meet the city’s obligations.

I went down to City Hall and met with outgoing City Manager T.C. Broadnax to double-check my math. Will we ever have enough money to pay for our aging infrastructure? And what about that “no new revenue” tax cut that Mayor Eric Johnson argued for in August, during discussions about the city’s budget? “The reality is,” Broadnax says, “the only way you can do and can perform what [the City Council] has asked us to do, with the current revenues and our expenses, is you’d have to make significant cuts to the services, I think, that people have come to like and expect and actually want more of. The balance is doing and managing all of those priorities with what we’ve got.”

“What we’ve got” is a set of zoning rules that have not been addressed holistically since 1967, when about half a million fewer people lived here. As Dallas grew and developers struggled with the outdated zoning, the City Plan Commission and the Council were forced to make ever more exceptions and adjustments for one project after another. The workarounds are called “planned development districts” or PDs. Some are complex and the result of years of planning, such as PD 193, 2,600 acres that encompass Oak Lawn and Uptown. The smallest is PD 1034, a .092-acre parcel at Prairie Avenue and Junius Street in Old East Dallas. We now have more than 1,000 PDs, and they cover about 17 percent of the city’s land mass.

Not counting those pesky PDs, which have multiplied beyond the city’s ability to analyze them, 42 percent of Dallas’ land is zoned to accommodate only single-family residential homes. Townhomes and duplexes are allowed on only 2.2 percent of Dallas’ land mass.

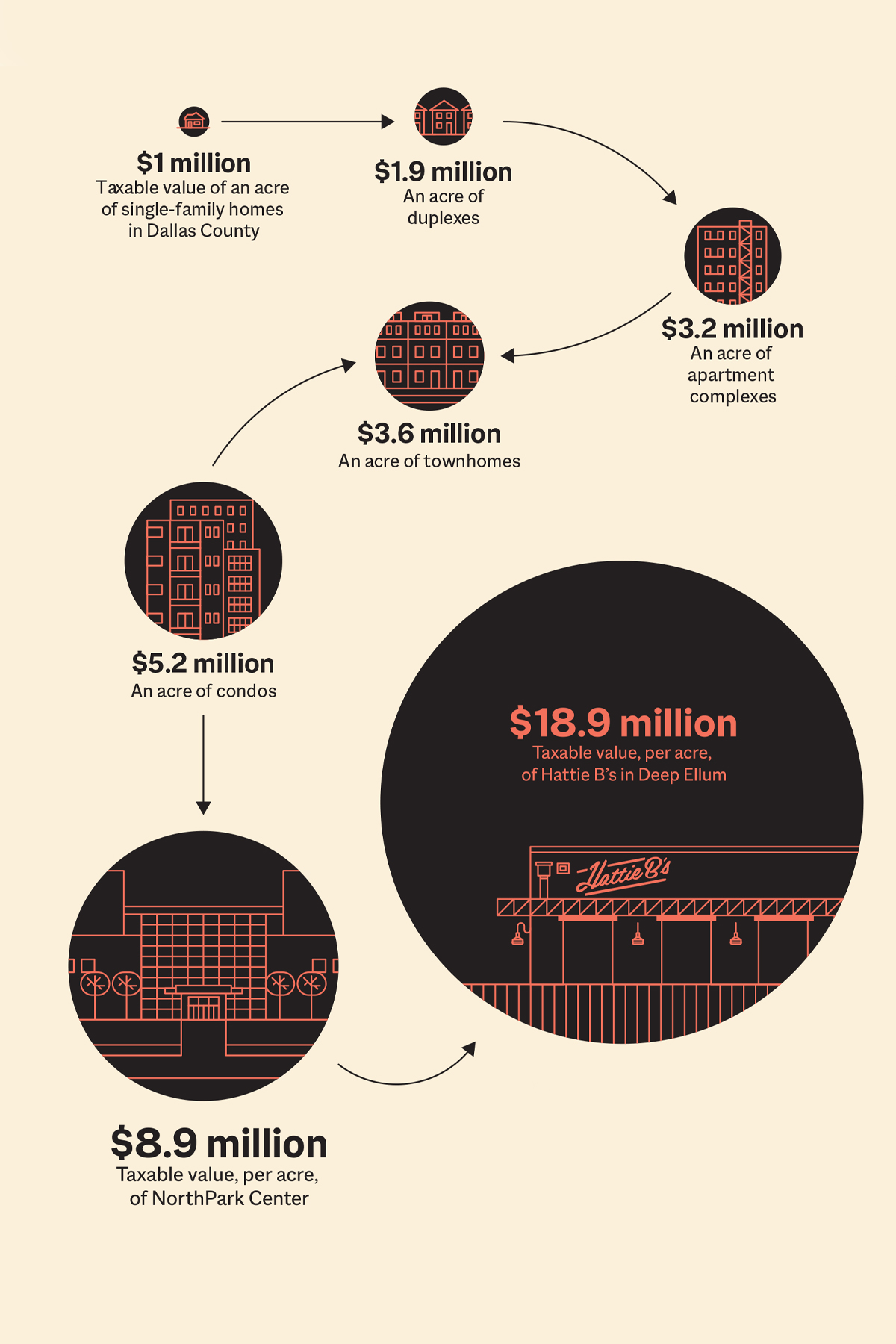

Minicozzi’s study shows how our outdated code is choking off the city’s revenue. On average, the taxable value of an acre of single-family homes in Dallas County is $1 million. An acre of duplexes is $1.9 million. Apartment complexes, $3.2 million. Townhomes, $3.6 million. Condos, $5.2 million. Dallas funds the vast majority of its budget through property tax (57 percent of total revenue) and sales tax (25 percent). State law prevents us from raising the sales tax any higher, so if we want to chip away at the $17 billion in unmet needs, we can periodically raise the real property tax rate or we can change how we use our land. We are leaving money in the ground.

Big developments are important, such as the recent corporate relocations in Uptown. But so are the incremental, smaller projects, the 1950s-era storefront sitting vacant, the lot that the zoning code deems too small for a house. It all adds up.

“I told the Mayor that we can’t have good city services, low taxes, and low density,” says Council Member Chad West, whose district includes the northern half of Oak Cliff. “If we want good city services and we want low taxes, we need to consider raising our density to pay for the city services.”

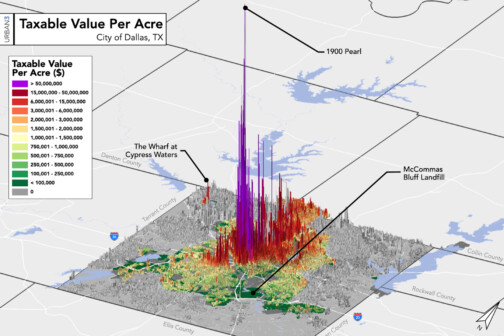

Let’s also take a quick look at commercial, remembering that Walmart’s average taxable value is $600,000 per acre. NorthPark Center’s taxable value is $8.9 million per acre. The taxable value of 1 acre of Hattie B’s, the hot chicken chain in Deep Ellum, is $18.9 million. Smaller developments make the most of the high-value land that surrounds them. Minicozzi is able to assign a dollar amount based on a complex analysis of each commercial use that takes into account tax exemptions, the history of the parcel, and the value of the surrounding land near the commercial product. He wants cities to look at what his map details; policymakers can draw their own conclusions as to where to encourage which types of development to get the most out of the land.

A menu of options begins to emerge. A 2023 study by the real estate software company Yardi Systems found that Dallas has more undeveloped land than any other American city, about 91,000 acres, the majority of which is in southern Dallas. Much of this part of the city was redlined, meaning that federal laws prevented banks from making loans there. It’s where Dallas has historically concentrated low-income housing projects and industrial uses. City planners are trying to solve this imbalance through the ForwardDallas process. The data show what can add the most value to the tax base while meeting the needs—housing, jobs, education—of the community. And, as Broadnax told me, maybe it’s time we figure out how to get more homeownership opportunities to residents in the south and more rental opportunities in the north. These are all decisions that cities must make, and Minicozzi’s study is another tool to consider.

The data are relevant in neighborhoods zoned for single-family, too. If duplexes are allowed on some of these blocks, the city can adjust height and design standards to give residents confidence that the duplex of today won’t turn into the 32-unit apartment complex of tomorrow. Meanwhile, new, light density can, over time, add additional value to the tax rolls.

“When we do land use evaluation in the city, we look at fire access, we look at height setback encroachments, we look at traffic and how it’s going to impact neighborhoods, access to schools,” West says, “but we don’t really ever talk about what the financial impact is to the city except generally. I think that [Minicozzi’s study] opened my eyes to us needing to do a little more than that.”

Other cities have heeded the data and math, and the results haven’t been catastrophic. Minneapolis recently eliminated parking requirements in new developments, rezoned commercial corridors to allow apartments, and approved duplex and triplex construction in all residential areas. From 2017 to 2022, according to the Pew Research Center, the city added 21,000 new units, and rent grew at just 1 percent compared to the statewide increase of 14 percent. And, by the way, duplex and triplex construction accounted for just 1 percent of those new units.

You don’t have to look far to find failing infrastructure in town. Take the intersection of Preston Road and Royal Lane. In October 2019, an EF3 tornado destroyed the Preston Royal Shopping Center. It also damaged a traffic light in the adjacent intersection. The city put up a temporary light structure, and then left it there—for four years. The permanent light was installed in November 2023.

I don’t think it will be difficult to spend some extra money.

This story originally appeared in the April issue of D Magazine. It originally contained a sentence comparing metro Atlanta to Dallas that couldn’t be fact checked and was therefore removed. Write to [email protected].

Author

Matt Goodman

View Profile

Matt Goodman is the online editorial director for D Magazine. He’s written about a surgeon who killed, a man who…